Summary: The decline of fertility rates with the advancement of economic and social development levels is a phenomenon observed universally across countries. Concurrently observed is the fact that if fertility rates remain at a low level for an extended period, it leads to continuous deepening of population aging. This, in turn, weakens the potential for economic growth and slows down the pace of socio-economic development. Due to researchers’ insufficient understanding of the determinants behind fertility rate changes, interpreting this asymmetric, even antagonistic, causal relationship seems challenging, forming the so-called “fertility paradox.” By referencing international experiences and analyzing China’s unique population transition, this article attempts to argue that the extremely low fertility rate currently observed in China is not inevitable. Through more comprehensive socio-economic development or by improving the Human Development Index, especially by addressing factors constraining family development and expanding family resource allocation curves, we can anticipate a rebound in fertility rates to replacement levels (which are also the desired levels), thereby breaking the fertility paradox.

摘要:生育率随经济社会发展水平的提高而下降,是一个各国普遍观察到的现象。同时观察到的事实则是,生育率长期处于较低水平,则导致人口老龄化不断加深,反过来削弱经济增长潜力,拖慢经济社会发展的步伐。由于研究者对于生育率变化决定因素的规律尚未充分认识,在解释这种不对称乃至对立的因果关系方面颇显捉襟见肘,构成一个所谓的“生育率悖论”。本文通过援引国际经验和分析中国的特殊人口转变过程,尝试揭示中国目前形成的极低生育率不是一种宿命。通过更完整的经济社会发展,或通过人类发展指数的提升,特别是有针对性地解决制约家庭发展的诸因素,拓展家庭资源预算曲线,可以预期生育率朝着更替水平(同时也是意愿水平)的反弹,从而打破生育率悖论。

I. Introduction

一、引言

By at least the 1940s, the theory of demographic transition had taken shape, persuasively revealing the trends and mechanisms of changes in birth rates and growth rates. It was anticipated that fertility rates would decrease with economic development (Caldwell, 1976). However, from the 1950s to the 1970s, academic and public opinion circles remained unaffected by this perspective. There was a prevailing deep concern about the “population explosion” in developing countries, leading to a flurry of radical calls for population growth controls. Representatives of this trend either had not encountered the theory of demographic transition or refused to accept its conclusions about declining birth rates. Hence, they failed to foresee that fertility rates would continually drop in both developed and developing countries after that time. Meanwhile, as a comprehensive indicator of economic development, the per capita GDP in both categories of countries saw a significant rise.

至少在20世纪40年代,人口转变理论便已经成型,富有说服力地揭示了人口出生率和增长率变化的趋势和机理,预期人口生育率将随着经济发展而降低(Caldwell, 1976)。然而,20世纪50年代到70年代的学术界和舆论界并未受其影响,仍然产生了对发展中国家“人口爆炸”的强烈担忧,并集中出现了一系列要求对人口增长采取控制手段的激进主张,一时间此类成果可谓汗牛充栋。这种思潮的代表性人物或者尚未接触到人口转变理论,或者不愿意接受其生育率下降的结论,因而也未能预见到自那之后,无论在发达国家还是在发展中国家,生育率均先后经历了持续的下降;与此同时,作为经济发展综合性指标的人均国内生产总值,在这两类国家都经历了大幅度的提高。

With the overall growth of the global economy and shifts in regional structures, economists, based on new empirical evidence, began to abandon various paradigms regarding the relationship between population and economic growth. Notably, they uncovered the significant contribution of the demographic dividend to economic growth. For instance, starting in the 1990s, economists, represented by some professors from Harvard University, conducted pioneering work in theoretical explanation and empirical verification. They discovered the significant contribution of the dependency ratio in economic growth, especially noting that this demographic factor played a crucial role in latecomer countries trying to catch up with the forerunners. This insight gave rise to the renowned demographic dividend school of thought. Some Chinese scholars also adopted this paradigm, finding through empirical studies that the demographic dividend displayed powerful explanatory prowess for the rapid growth during China’s reform and opening-up period.

随着世界经济整体增长以及区域格局的变化,经济学家根据新的经验证据,开始摒弃各种版本关于人口与经济增长关系的研究范式,特别是揭示了人口红利对经济增长的显著贡献。例如,从20世纪90年代开始,以一些哈佛大学教授为代表的经济学家,在理论解释和经验验证方面做了一系列开创性的工作,在研究中发现了人口抚养比在经济增长中的显著贡献,特别是发现以这个变量为代表的人口因素,在后起国家赶超先行国家的发展过程中发挥了决定性的作用,由此形成了著名的人口红利学派。一些中国问题研究者也借鉴了这种研究范式,通过经验研究发现人口红利的贡献,显示这个理论对于中国改革开放时期的高速增长源泉,具有极强的解释力。

For developing or catching-up countries, the demographic dividend theory remains the most compelling and relevant population economics doctrine, providing a beneficial research paradigm for scholars. However, like any economic theory with explanatory power for specific periods or issues, it cannot universally address all matters at all times. We should not expect the demographic dividend theory to be a panacea unlocking the enigma of the relationship between population and the economy. In reality, due to the inherent limitations of the theory, when facing new challenges emerging in the new stages of demographic transition, it reveals certain inadequacies both in theoretical explanation and policy recommendation. This article will briefly outline such limitations of the demographic dividend theory to foster a more open-minded approach, drawing from various complementary analytical frameworks and tools. By integrating historical, theoretical, and practical logic, we aim to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between the population and the economy, subsequently proposing beneficial and effective policy recommendations.

至少对于发展中国家或赶超型国家的发展实践,人口红利理论是迄今人口经济学诸家学说中理论解释力最强、也最贴近经济发展特征化事实的一个研究流派,也为学者提供了有益的研究范式。然而,正如在特定时期、针对特定问题具有解释力的经济学理论,终究不可能在任何时点上总能包打天下,我们也不应该苛求人口红利理论成为解锁人口与经济关系之谜的万能钥匙。实际上,由于该理论本身存在的先天不足,面对人口转变新阶段上出现的新问题,在理论解释和政策建议上显现出一定程度的捉襟见肘。下面,本文简单概括人口红利理论的这类不足,以便能够以更加开放的态度,借鉴各种可供互补的分析框架和分析工具,结合历史逻辑、理论逻辑及现实逻辑对人口与经济关系做出更全面的认识,进而为解决当前的问题提出有益和有效的政策建议。

First, there is a lack of a strong connection between the demographic dividend research paradigm and mainstream growth theories, inevitably reducing its breadth and depth in understanding the relationship between population and growth. This limitation in research is evident in the selection of variables that directly impact economic growth due to population factors. For instance, most studies use the population dependency ratio as a proxy for the demographic dividend and incorporate it into economic growth models to observe its significance and magnitude. As a result, the demographic dividend research confines its analytical scope, failing to recognize variables beyond the dependency ratio. Many traditional variables used in growth accounting and growth regressions are, in fact, related to population factors.

首先,人口红利研究范式与主流增长理论之间缺乏良好的衔接,不可避免地降低了自身认识人口与增长关系问题的广度和深度。这方面的研究局限表现在对人口因素直接影响经济增长的变量选取上面。例如,大多数研究用人口抚养比作为人口红利的代理变量,将其纳入经济增长核算模型,观察其影响的显著性和幅度。这样,人口红利研究便把分析范围做了自我限制,未能看到抚养比这个人口变量之外的变量,甚至很多增长核算和增长回归中采用的传统变量,其实也是与人口因素相关的。

In reality, demographic changes, especially shifts in age structures, not only influence labor supply but also impact the rate of improvement in human capital, savings rates, returns on capital, and the efficiency of resource reallocation, which subsequently affects labor productivity and total factor productivity (Cai, 2019). Due to a lack of alignment with neoclassical growth theory, this paradigm missed the opportunity to revolutionize or significantly modify the former, leading the demographic dividend theory to remain relatively marginal in growth theories.

实际上,人口变化特别是年龄结构的变化不仅影响劳动力供给,还影响人力资本改善速度、储蓄率和资本回报率、资源重新配置效率进而影响劳动生产率和全要素生产率等(Cai, 2019)。由于未能在与新古典增长理论逻辑进行衔接的基础上充分理解进而解释清楚人口红利,这种理论范式便失去对前者进行颠覆性修正或革命性发展的良好机会,使人口红利理论在增长理论中始终处于相对边缘的地位。

Second, the demographic dividend research paradigm solely focuses on the supply-side effects of population factors on economic growth, neglecting demand-side effects. Indeed, for a long time, economic development patterns witnessed in many countries and regions were largely driven by harnessing the demographic dividend from the supply side, leading to extraordinarily high growth rates. Thus, theories and empirical studies in this field either validate the experience of the demographic dividend boosting potential growth or highlight the fact that growth rates will decline once the demographic dividend disappears.

其次,人口红利研究范式仅仅关注人口因素影响经济增长的供给侧效应,而尚未进入研究需求侧效应的层面。诚然,在很长的时间里人们观察的经济发展事实,大多是一些国家和地区通过兑现人口红利,从供给侧获得额外的增长源泉,实现超常规的高速增长。因此,这个领域的理论假设和经验研究,一方面,是论证和检验人口红利提高潜在增长能力的经验;另一方面,则是警示和揭示人口红利消失后潜在增长率将会降低的事实。

However, with the global aging of the population and some developed economies entering an era of negative population growth, the impact of demographic factors is now more pronounced on the demand side. Whether it is pioneer countries in demographic transition, like Japan, or the trend already evident in China as a follower, both indicate that in the two crucial turning points of demographic change, the first—the peak of the working-age population—mainly affects economic growth from the supply side. In contrast, the second turning point, the peak of the total population, has a more pronounced impact on the demand side of economic growth. If the factors on the demand side can be integrated into the logic of the demographic dividend theory, the theory’s relevance and explanatory power regarding reality can be significantly enhanced. On the one hand, it can find common ground with the mainstream proposition of long-term stagnation. On the other hand, it can make a unique contribution to the study of this proposition, further refining and enriching its theoretical framework.

然而,随着全球范围人口老龄化,以及一些发达经济体进入人口负增长时代,人口因素带来新的冲击更多表现在需求侧。无论是如日本这样的人口转变先行国家,还是中国作为赶超者迄今已经呈现的趋势,都表明在人口转变的两个重要转折点中,第一个转折点即劳动年龄人口峰值,主要从供给方面造成对经济增长的冲击,而第二个转折点即总人口峰值,对经济增长的需求侧冲击效应则更为突出。如果能够把需求侧的因素统一到人口红利理论的逻辑中,该理论对现实的针对性和解释力可以显著增强。一方面,可以与长期停滞这个主流的命题找到共同点;另一方面,也可以在对该命题的研究做出独特贡献的同时,进一步完善和充实自身理论框架。

Furthermore, the demographic dividend research paradigm tends to eternalize the demographic dividend. Given that the dependency ratio is used as a quantitative indicator of the demographic dividend, according to the logic and process of demographic transition, this factor will eventually reverse in a direction unfavorable to economic growth. Hence, prominent authors in this field proposed the concept of a second demographic dividend, deviating from the previous logical trajectory. They mainly discuss the second demographic dividend from the perspective of maintaining savings levels, believing that a population consisting more of older workers and elderly will have a strong savings motivation, thus sustaining economic growth. In their view, as the effect of the first demographic dividend wanes, the second demographic dividend will emerge and persist forever. However, this so-called second demographic dividend theory has flaws in both methodology and relevance to reality. On the one hand, the source of their proposed second demographic dividend does not come from favorable demographic factors, which weakens the demographic dividend theory itself. On the other hand, the significant challenge brought by aging is not insufficient savings but excessive savings, a primary feature of long-term stagnation. Thus, this so-called second demographic dividend is not genuinely a “dividend” to be reaped.

再次,人口红利研究范式具有把人口红利永恒化的倾向。既然以抚养比作为人口红利的定量性指标,按照人口转变的逻辑和进程,这个因素终究会逆转到不利于经济增长的方向。于是,这个领域的代表性作者提出第二次人口红利的概念,便脱离了以往的逻辑轨道。他们主要从保持储蓄水平的角度探讨第二次人口红利,认为由更多大龄劳动者和老年人口组成的人口,将会产生强大的储蓄动机,因而保持经济增长源泉。在他们看来,随着第一次人口红利的作用发挥殆尽,第二次人口红利随即出现并将永远地存在下去。这种所谓第二次人口红利理论,分别在方法论上和现实针对性上存在着缺陷。一方面,他们认为的第二次人口红利源泉,并不是来自有利的人口因素,这种泛人口红利论实际上会削弱人口红利理论本身。另一方面,事实上老龄化带来的重大挑战并不是储蓄不足,而是作为长期停滞主要特征之一的过度储蓄。因而,这种所谓的第二次人口红利,其实并不是什么所要收获的“红利”。

Last, the demographic dividend research paradigm has not devoted enough passion and resources to the topic of how to stimulate fertility rates to bounce back to replacement levels. Given that the theoretical framework itself is based on unidirectional changes in fertility rates, expecting breakthroughs in research on increasing fertility might be unrealistic. However, this creates a theoretical dilemma known as the “fertility paradox,” which researchers ultimately need to address. This article examines the paradox on three levels: First, while economic and social development lead to reduced fertility rates, once they decrease to a certain extent, they hinder economic and social progress. Second, similar to the above logic, although fertility rates can be viewed as a function of economic and social development indicators, when considering dynamic time changes and other exogenous factors, it is impossible to conclude that economic and social growth is the inverse function of fertility rates. Third, the relationship between fertility rates and economic and social development is neither linear nor unlimited. In fact, although many countries have total fertility rates breaking through the 2.1 replacement level, situations with a total fertility rate below 1 are rare. From these perspectives, the so-called fertility paradox reflects people’s understanding at a particular stage, or it poses an unresolved proposition, hoping to gain more attention from researchers.

最后,人口红利研究范式没有在如何推动生育率向更替水平方向反弹这个课题上面投入足够的研究热情和研究资源。鉴于这个理论框架本身就是以生育率单向变化为基础的,希冀其在生育率回升问题的研究上取得突破或许并不现实。但是,由此而产生一个理论上的难点即“生育率悖论”,终究需要研究者给出答案。本文可以从三个层次上看这个悖论:第一,生育率因经济社会发展而降低,但是在其降低到一定程度后,却反过来阻碍经济社会发展;第二,与上面这个逻辑相似的是,生育率虽然可以被看作是经济社会发展指标的函数,然而,一旦把时间的动态变化,以及其他外生的影响因素考虑在内,却无法得出经济社会发展是生育率的反函数的结论;第三,生育率和经济社会发展之间的关系既不是线性的,也不是没有下限的。实际上,虽然在诸多国家总和生育率都突破了2.1这个更替水平,但是迄今总和生育率低于1的情形却极为鲜见。从这些方面来看,所谓的生育率悖论,其实反映的是人们在特定阶段的一种认识状态,或者说只是提出一个未解的命题,希望得到研究者的更多关注。

While this proposition involves a general phenomenon common to many countries, this article focuses more on exploring the specificity of China’s experience and targeted solutions from general rules. Although, in the end, it is the different stages of declining fertility rates that determine the emergence and disappearance of the demographic dividend, the demographic transition in different countries still has its unique characteristics and differences. For example, the decline in China’s fertility rate is both a result of the general trend where economic and social development acts as a basic driving force, and is also uniquely influenced by the strictly enforced one-child policy. Therefore, the current extremely low total fertility rate might contain historical influences where fertility desires were suppressed. Hence, exploring the potential for a rebound in fertility rates is warranted, both from a general standpoint and considering China’s unique context.

这个命题固然涉及各国都存在的一般现象,本文则更着眼于从一般规律中探寻中国经验的特殊性和具有针对性的解决方案。虽然归根结底是生育率下降的不同阶段决定了人口红利的出现和消失,但是,不同国家人口转变仍然存在差异性和独特性。例如,中国生育率的下降,既是经济社会发展作为基本驱动力这个一般规律的结果,也受到严格执行的计划生育政策的特有影响。因此,目前极低的总和生育率,很可能包含着生育意愿受到抑制的历史影响。也就是说,无论是从一般规律的角度,还是从国家特殊性的角度,都值得对生育率反弹的可能性进行探索。

Moreover, in academia, there is a research tendency to dismiss studies that suggest a negative impact of population aging on economic growth. These dismissals typically employ the following signature argument methods: 1. In response to the fact that the working-age population is declining, they usually point out that the overall scale of the working-age population remains large, thereby denying the adverse effects of the weakening or disappearance of the demographic dividend. 2. With regards to the expectation that the population will peak and then enter negative growth, they often argue that the overall scale of the population will still be large enough, negating any warning of adverse effects. 3. In the face of labor shortages and weakening comparative advantages, they often suggest that enhancing human capital can improve the quality of workers, thus compensating for the shortage in numbers. For example, a recent study concluded that a low fertility rate would not hinder China’s economic growth. The basic argument is that, even with aging, economic growth can still be promoted by improving human capital, labor participation rate, and productivity. The policy implication is that China should not focus on seeking to increase fertility. Such studies, due to their methodological flaws, inevitably lead to misunderstandings of other research conclusions, which could potentially mislead with their findings.

此外,在学术界还有一种研究倾向,即针对关于人口老龄化对经济增长不利影响的研究,一味地持否定的态度,往往采用以下这些标志性的论证方法:第一,针对劳动年龄人口负增长的事实,通常会指出劳动年龄人口的总规模将保持庞大,以此否认人口红利减弱或消失的不利影响;第二,针对人口数量达到峰值进而转入负增长的预期,通常会指出人口总规模将足够大,以此否定任何不利的警示;第三,针对劳动力短缺从而比较优势减弱的事实,通常会指出强化人力资本可以提高劳动者质量,从而弥补数量的不足。例如,一项最新的研究认为,低生育率不会阻碍中国经济增长的结论。其基本论证就是如此,即在老龄化条件下,仍然可以通过提高人力资本、劳动参与率和生产率促进经济增长。政策含义则是,中国不应该把政策重点放在寻求提高生育率上面。这类研究因其方法论的缺陷,不可避免产生对其他研究结论的一些误解,因而自身的结论也就难免产生误导。

First, when highlighting negative trends like the disappearance of the demographic dividend, a basic methodological premise assumes that other conditions remain unchanged, and solely because of population structure changes, economic growth suffers a blow. Aging is undoubtedly linked to labor shortages, but it does not necessarily correspond to accelerated improvements in human capital, labor participation rate, and productivity. Pointing out the challenges of the disappearing demographic dividend merely highlights the factors that once drove rapid economic growth are weakening or have been lost. It also emphasizes the need to explore other more sustainable sources of growth.

首先,当人们揭示一种诸如人口红利消失这样的不利变化倾向时,一个基础性的方法论前提,便是假设在其他条件不变的情况下,仅因人口结构的变化会使经济增长遭受冲击。老龄化无疑是与劳动力短缺相联系的现象,同时却并不注定是与人力资本改善加快、劳动参与率和生产率加快提高相伴随。所以,指出人口红利消失的挑战,无非是提示以往推动经济高速增长的因素正在或已经丧失,同时并不否定,反而恰恰是为了强调探寻其他更可持续增长源泉的必要性和紧迫性。

Second, indeed, under the conditions of a disappearing demographic dividend, many other economic growth factors also reverse. Macroeconomically, the economy can no longer maintain its past growth rate. For instance, with the reduction of new labor entering the workforce, the speed at which human capital among existing workers improves significantly slows. The proportion of the older population and older workers naturally tends to lower the labor participation rate. With the weakening and loss of traditional comparative advantages, it becomes easy for low-productivity enterprises to stay in business, leading to resource allocation rigidity. A premature reduction in manufacturing weight, coupled with too rapid and premature a shift of the labor force to lower productivity services, causes resource allocation degeneration, making productivity improvements more challenging (Cai Fang, 2021b).

其次,事实上,恰恰是在人口红利消失的条件下,其他诸多经济增长因素也发生逆转,在宏观意义上的生产函数中显示出,经济不再能够保持以往的增长速度。例如,随着新成长劳动力的减少,劳动力存量的人力资本改善速度显著减慢;老年人口和大龄劳动力比重提高,天然地具有降低劳动参与率的效果;随着传统比较优势的弱化和丧失,容易产生低生产率企业不能退出经营,形成资源配置的僵化;制造业比重早熟型降低,劳动力出现过快过早向生产率更低的服务业转移,造成资源配置的退化,都使生产率提高遭遇更大的困难(蔡昉,2021b)。

Last, while China’s economic future should not solely rely on increasing fertility rates, boosting fertility rates does not hinder human capital accumulation, labor participation rate improvements, or productivity enhancements. In fact, policies aiming to increase fertility align with these objectives, a point further explored and validated in this article.

最后,中国经济发展的前途固然不能把宝完全押在生育率的提高上面,但是,撇开人们的生育意愿可能受到某些因素的抑制不说,提高生育率的政策努力并不妨碍人力资本的积累、劳动参与率的提高和生产率的改善。事实上,提高生育率的政策意图与这类目标恰恰是相容和一致的。这个观点将在本文的其他部分予以论证和检验。

Hence, this article will both highlight the long-term challenges brought about by China’s low fertility rate and discuss the possibility of boosting fertility rates through reforms and policy adjustments. In the second section, this article will discuss the conditions under which a declining fertility trend could rebound or rise again, looking at general trends and international experiences. International experiences show these conditions prominently manifest when gender equality gains more attention at high human development levels. The third section, using international experience, will discuss China’s challenges and urgency in entering a deeper stage of aging, transitioning from an aging society to an aged society. The fourth section will argue that an extremely low fertility rate is not China’s fate. By analyzing the constraints on family development, we reveal opportunities to tap into fertility potential. The fifth section will provide a summary of this article’s conclusions and discuss their policy implications.

因此,本文将既指出中国低生育率带来的长期挑战,也探讨通过改革和政策调整促使生育率反弹的可能性。在第二部分,本文将从一般趋势和国际经验的角度,讨论趋势性下降的生育率可能出现反弹或回升的条件。国际经验表明,这些条件最突出地表现为性别平等得到更加关注的高度人类发展水平。第三部分结合国际经验讨论中国在进入程度更深的老龄化阶段,即从老龄化社会转变到老龄社会的新挑战和应对的紧迫性。第四部分重点论证极低生育率并不是中国的宿命,从分析家庭发展的制约因素着眼,揭示出可以挖掘生育潜力的机会。第五部分是对本文的结论进行概括,并讨论其政策含义。

II. Can the birth rate only decrease linearly and monotonically?

二、生育率只能线性且单调下降吗?

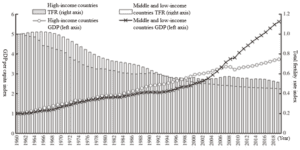

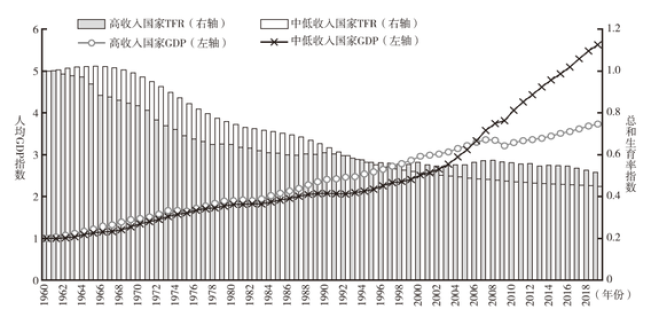

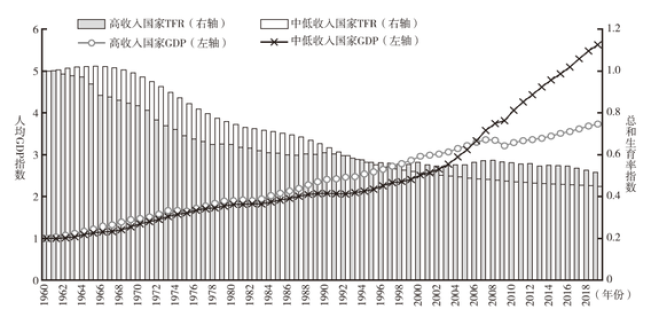

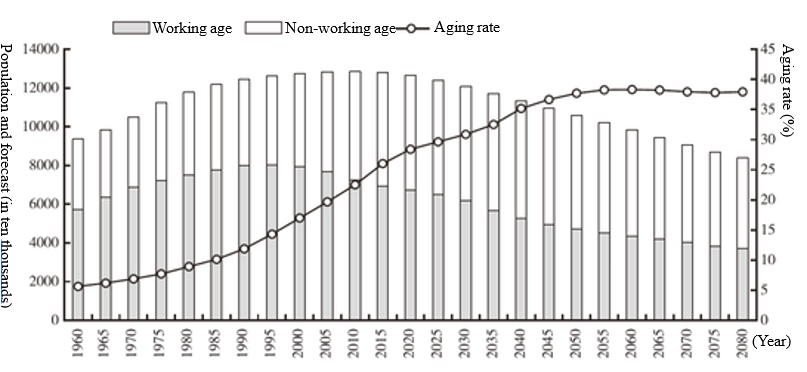

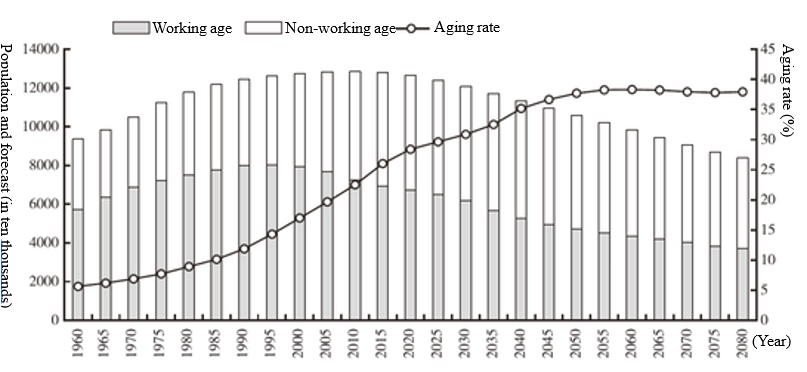

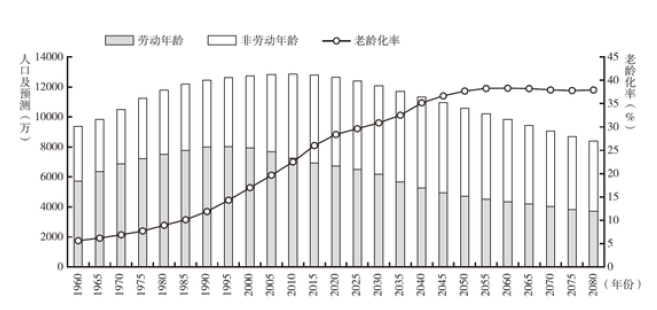

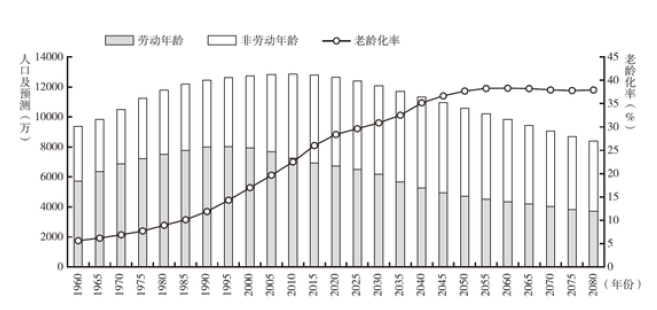

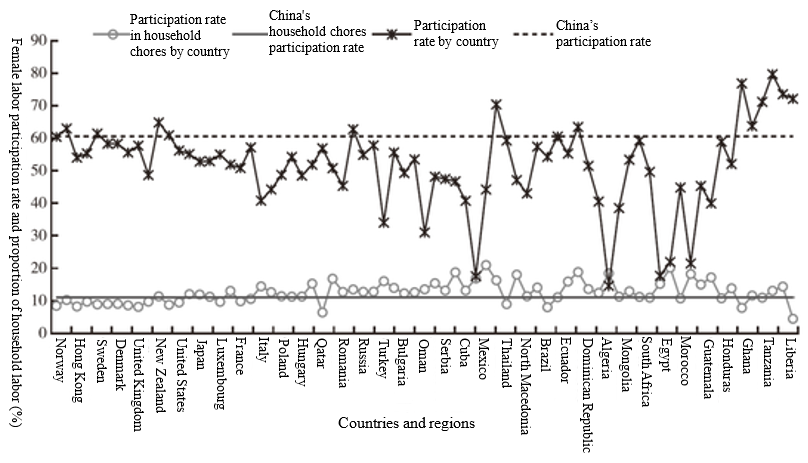

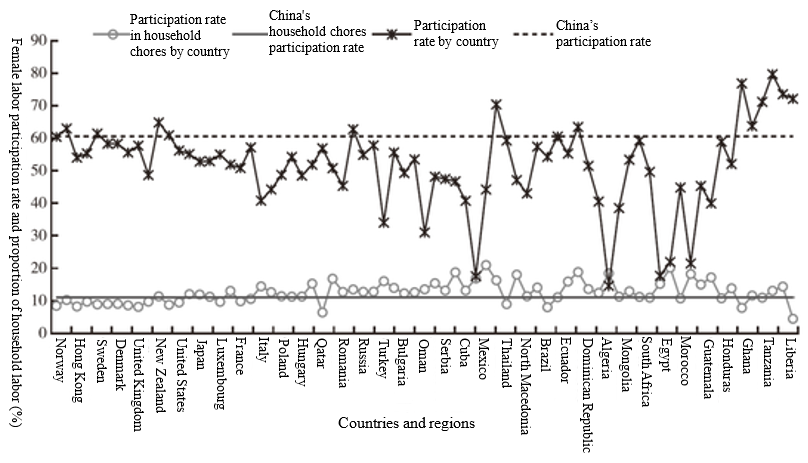

With the increase in per capita income, the continuous decline in the fertility rate has become a widely observed fact. In Figure 1, based on World Bank data and definitions, countries are divided into two categories: high-income countries and low to middle-income countries. The relationship between per capita income and total fertility rate (TFR) is shown. Figure 1 presents the change in the per capita GDP index and TFR index with 1960 as the base year. Here, the per capita GDP is calculated in constant 2015 U.S. dollars, and the TFR refers to the average number of children a woman will give birth to in her lifetime. It can be seen from Figure 1 that since 1960, as per capita GDP continued to grow in high-income countries, TFR continued to decrease; in low and middle-income countries, as the per capita GDP caught up, TFR also began to decline from the mid-1960s and did so at a more noticeable rate.

随着人均收入的提高,生育率持续性下降,已经成为一个普遍观察到的特征化事实。在图1中,本文根据世界银行数据和定义,分两类国家即一类为高收入国家,另一类为低收入和中等收入国家,展示人均收入与总和生育率之间的关系。图1中展示的是以1960年为基期的人均GDP指数和总和生育率指数变化。其中,人均GDP是按照2015年不变美元计算,总和生育率(TFR)系指平均每个妇女终身生育的孩子数。从图1中可见,自1960年以来,高收入国家在人均GDP继续增长的同时,TFR持续降低;低收入和中等收入国家在人均GDP赶超增长的同时,TFR从20世纪60年代中期之后也开始降低,并且以更明显的幅度进行。

Furthermore, based on the World Bank’s classification, countries can be grouped into high-income, upper-middle-income, lower-middle-income, and low-income categories. The changes in per capita income and fertility rate within these groups are observed. In 1960, high-income countries had an average per capita GDP of $11,518 and a TFR of 3.03. Later, by 1975, the fertility rate dropped below the replacement level of 2.10, with a per capita GDP of $19,006. By 2019, the average per capita GDP for this group reached $43,001, with a TFR reduced to 1.57. The TFR for upper-middle-income countries started to decline from a base of 5.53 in 1965, when the average per capita GDP was $1,326. By 1994, when the per capita GDP reached $2,990, the TFR dropped below the replacement level. In 2019, the per capita GDP was $9,527, with a TFR of 1.83. The TFR for lower-middle-income countries began to decline from a base of 5.98 in 1962 when the average per capita GDP was just $626. By 2019, with a per capita GDP of $2,365, the TFR was 2.69, still above the replacement level. The TFR for low-income countries began to decline from a base of 6.75 in 1972. The World Bank database does not have the average per capita GDP data for these countries for that year. In 2019, the per capita GDP for low-income countries was $745, with a TFR of 4.57, which is significantly higher than the replacement level.

进一步,本文还可以根据世界银行的定义,分别从高收入、中等偏上收入、中等偏下收入和低收入四类国家分组,观察人均收入增长与生育率变化情况。高收入国家平均人均GDP在1960年已经达到11518美元,TFR为3.03。随后,在1975年生育率下降到可以维持人口稳定的更替水平2.10之下,这一年的人均GDP为19006美元;2019年,这组国家的人均GDP平均水平为43001美元,TFR降低到1.57。中等偏上收入国家的TFR从1965年5.53的基础上开始降低,这一年的平均人均GDP为1326美元;1994年在人均GDP达到2990美元时,TFR降到更替水平之下;2019年人均GDP为9527美元,TFR降低到1.83。中等偏下收入国家的TFR是在1962年5.98的基础上开始降低,当年人均GDP仅为626美元;2019年人均GDP提高到2365美元的情况下,TFR为2.69,仍在更替水平之上。低收入国家的TFR是在1972年6.75的基础上开始下降,世界银行数据库中没有这组国家当年的人均GDP平均数据;2019年低收入国家人均GDP为745美元,TFR为4.57,仍然大幅度高于更替水平。

It is generally believed that since the 1950s, the global economy has entered an era of convergence (Spence, 2011). Since the 1990s, with the onset of a new wave of economic globalization, the world’s economy has also shown obvious convergence. In other words, developing countries achieved a faster per capita GDP growth rate than developed countries (Cai Fang, 2019). Another perspective on this development fact is that the rate of decline in fertility in developing countries is significantly faster than in developed countries. The universal decline in global fertility rates will inevitably lead to global population aging. According to the revised 2019 population data provided by the United Nations, the proportion of the world’s population aged 65 and over (i.e., the aging rate) increased from 4.97% in 1960 to 9.32% in 2020. Furthermore, the average aging rate of all four income group countries has increased. Among them, high-income and upper-middle-income countries have the highest degree of aging, reaching 18.6% and 11.1% in 2020, respectively (UNDESA, 2019).

一般认为,20世纪50年代以后世界经济进入一个大趋同的时代(Spence, 2011),90年代之后在经济全球化进入新一轮高潮期间,世界经济也呈现出明显的趋同。也就是说,发展中国家总体上实现了比发达国家更快的人均GDP增长(蔡昉,2019)。这个发展事实的另一个角度,则是发展中国家生育率的下降速度也显著快于发达国家。全世界生育率的普遍下降,最终必然导致全球人口的老龄化。根据联合国提供的2019年修订版人口数据,全世界65岁及以上人口占比(即老龄化率)从1960年的4.97%提高到了2020年的9.32%。而且,所有四个收入组国家的平均老龄化率都提高了,其中,高收入国家和中等偏上收入国家老龄化程度最高,2020年分别达到18.6%和11.1%(UNDESA, 2019)。

Although there are still significant differences among countries, the adverse effects of population trends on economic growth have received widespread attention and have become an essential research topic in academia. Related research includes discussions in two directions: first, since the population transition is ultimately a regular and inevitable trend, there is a need to study how to address the long-term stagnation of economic growth in the context of aging, especially how to deal with the characteristics of the new normal in the world economy, such as low inflation, low long-term interest rates, and low economic growth rates. Second, the continuous decline in fertility may not necessarily be a universal fate. At least for some countries, there is still an opportunity to slow down the rapid decline in fertility and even to achieve a rebound in fertility to some extent and for some time.

虽然各国之间仍然有着巨大的差异,但是,人口变化趋势对经济增长的不利影响已经得到广泛的关注,也成为学术界的一个重要研究课题。这些相关的研究包括在两个方向上进行的讨论:其一,既然人口转变归根结底是符合规律的必然趋势,因此,需要研究如何在老龄化背景下应对经济增长的长期停滞现象,特别是应对低通货膨胀率、低长期利率和低经济增长率这些刻画世界经济新常态的特征;其二,生育率的持续下降未必是一种普遍性的宿命,至少就一些国家而言,仍然有机会延缓生育率的过快降低,甚至在一定程度上以及在一段时间内实现生育率的反弹。

From an economic perspective, when discussing how to eliminate the obstructive effects of population changes on economic growth, it is also necessary to look at the inherent patterns of population changes and see what potential can be tapped to encourage the fertility rate to rebound to replacement levels. To reverse population aging, we ultimately need the fertility rate to return to above replacement levels. This seems like an “impossible task.” Perhaps some might think that serious researchers and policymakers who face reality should not set themselves the goal of returning to replacement-level fertility. So, what should be the realistic target for fertility rates? We can look at the current state of fertility rates worldwide, the gap between this status quo and potential fertility intentions, and the relevant determining factors.

在从经济学角度探讨如何消除人口变化对经济增长产生的阻碍效应的同时,也有必要从人口自身的变化规律,看一看有什么可以挖掘的潜力,促使生育率朝着更替水平回升。人口老龄化要想逆转,终究需要生育率回归到更替水平之上。这似乎是一个“不可能的任务”。或许有人会认为,严肃的研究者和正视现实的政策制定者,并不应该给自己提出回归更替水平生育率的目标。那么,应该提出怎样的生育率目标,才算是现实可行的呢?可以从世界范围看一看生育率现状、这个现状与可能的生育意愿之间的差距,以及相关的决定因素。

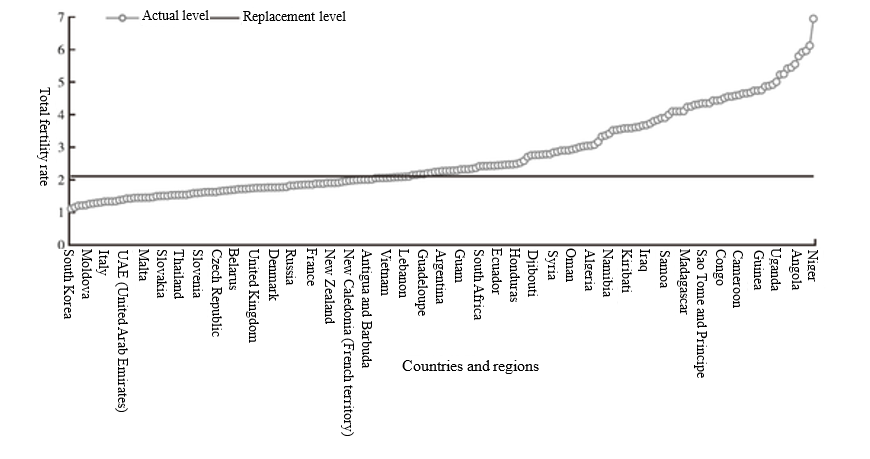

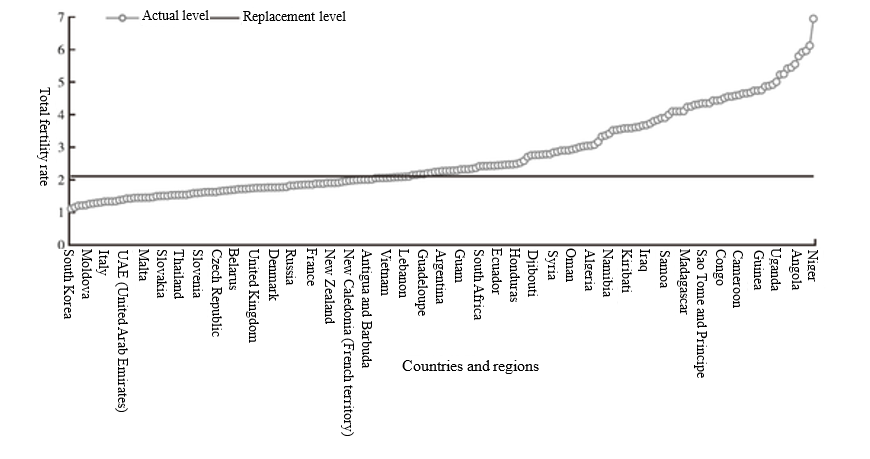

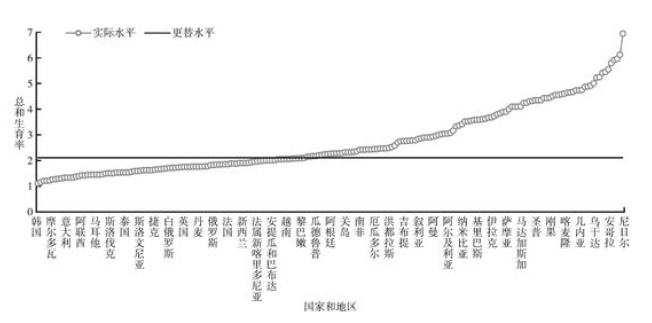

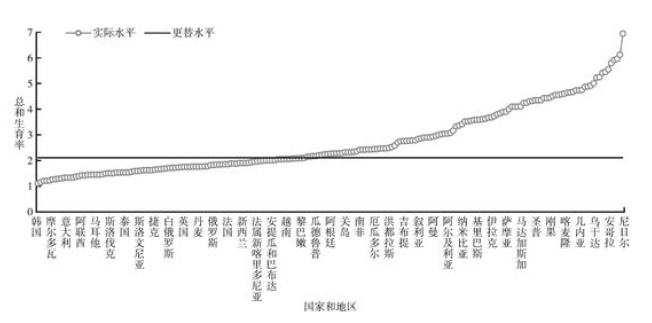

The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs’ Population Division found from many surveys that regardless of whether the current fertility rate is high or low, households in all countries tend to express a fertility preference of about two children. That is, in the absence of particular constraints, the desired fertility rate is generally consistent with the replacement-level fertility rate. Figure 2, which shows the relationship between the actual TFR of countries and the replacement-level TFR, can be combined to see which factors promote or constrain the actual fertility rate’s convergence to the preference level for countries with high and low fertility rates.

联合国经济和社会事务部人口司从诸多调查中发现,无论当下的生育率是高是低,各国受访家庭倾向于表达出的生育偏好大约为两个孩子。也就是说,在不存在特别的制约因素的条件下,意愿生育率大体上与更替水平生育率是一致的。可以结合图2显示的各国实际TFR与更替水平TFR之间的关系,看一看对于高生育率国家和低生育率国家来说,分别是哪些因素促进或制约实际生育率向偏好水平收敛。

Countries that currently have high fertility rates have largely experienced a gradual decline in fertility. This corresponds with the rapid economic growth and significant poverty reduction in developing countries. This can be directly observed through cross-national data. Additionally, based on data from the World Bank, this article compares the “desired fertility rate” and the actual fertility rate of dozens of low and middle-income countries. The simple average of these two fertility rates in these countries are 3.26 and 3.78, respectively. This means that if unwanted births could be prevented, the average number of children born in these countries and regions could be reduced by 0.52, or a 13.7% reduction in fertility rate. Furthermore, the poorer the country, the greater the disparity between the desired and actual number of children. For example, in the least developed countries, as defined by the United Nations, the desired fertility rate is 3.41, while the actual fertility rate is 4.06. A study based on population trends in 195 countries and regions indicates that the long-term decline in fertility rates in such countries is largely attributed to the increased level of women’s education and the availability of contraceptives, accounting for 80%.

目前仍然具有高生育率的国家,大多也经历了生育率的逐年下降过程,恰好与发展中国家加快经济增长、大幅度减贫的过程相对应。这些都可以通过跨国数据予以直接观察。此外,根据世界银行提供的数据,本文对比了数十个低收入和中等收入国家的“希望生育率”和实际生育率,这些国家这两个生育率的简单平均值分别为3.26和3.78。也就是说,如果能够避免那些家庭并不希望出生的孩子数,这些国家和地区的平均生育孩子数可以减少0.52个,或者生育率降低13.7%。而且,越是贫穷的国家,希望的孩子数与实际的孩子数之间差别越大,例如,在联合国定义的最不发达国家,希望生育率为3.41,而实际生育率为4.06。一篇根据对195个国家和地区人口趋势进行研究的论文指出,这类国家生育率长期下降的驱动力,80%可归结为妇女受教育程度和避孕用具可获得性的提高。

Research shows that for countries with low fertility rates, addressing or eliminating factors hindering childbirth, such as promoting gender equality, empowering women, and improving reproductive health services, can potentially lead to a moderate rebound in fertility rates (UNDESA, 2019). In particular, studies have shown that indicators of human development, including GDP per capita, education levels, and life expectancy, not only contribute to decreasing fertility rates over a certain period but may also be conditions for a rebound at higher levels. Using long-term data from over 100 countries, researchers have found that if high human development levels are achieved and gender equality is ensured, fertility rates among women in their later reproductive years will increase. In other words, without gender equality, general improvements in human development are not enough to boost fertility rates. The conclusion is that a balance between work and family life is essential to increase fertility rates.

研究表明,对于那些低生育率国家来说,如果能够处理好或者消除阻碍生育的因素,如促进性别平等和妇女赋权以及提高生育健康服务等,生育率依然可望实现适度反弹(UNDESA, 2019)。特别是有研究表明,包括人均GDP、受教育水平、预期寿命等生活质量内容在内的人类发展水平,既是一定时期内生育率下降的诱因,也可能在更高水平下成为生育率反弹的条件。这些作者利用100多个国家的长期数据揭示,如果在实现很高的人类发展水平的同时,还能够满足性别平等这个条件,女性在其生殖年龄稍晚时期的生育率会得到提高。也就是说,不具备性别平等这个条件的话,仅有人类发展水平的一般性提高,也不足以促使生育率出现反弹。由此得出的结论是,提高生育率需要处理好工作和家庭的平衡关系。

III. Transition from an Aging Society to an Aged Society

三、从老龄化社会到老龄社会的转变

Defining aging on an international comparative scale, or differentiating the degree of aging, requires quantitative descriptions. In a 1956 report, the United Nations first defined populations from an age perspective, categorizing populations with an aging rate below 4% as “young,” between 4% and 7% as “mature,” and above 7% as “aged” (UNDESA, 1956). Later, it is generally believed that the World Health Organization further delineated aging degrees: countries or regions with an aging rate over 7% are defined as an “aging society,” over 14% as an “aged society,” and over 21% as a “super-aged society” (cited from Okamura, 2016).

在国际比较的层面上定义老龄化也好,区分老龄化的程度也好,都需要一些定量性的描述。联合国在1956年的一份报告中,第一次从年龄构成的角度界定人口类型,把老龄化率在4%以下的人口称为“年轻型”(young),4%~7%之间为“成熟型”(mature),7%以上为“老龄型”(aged)(UNDESA, 1956)。后来,一般认为世界卫生组织进一步对老龄化做出了程度上的划分,即老龄化率超过7%的国家或地区被定义为“老龄化社会”(aging society),老龄化率超过14%为“老龄社会”(aged society),老龄化率超过21%便是进入了“极度老龄社会”(super-aged society)(转引自Okamura, 2016)。

China’s aging rate reached 7.0% in 2000, marking its entry into an aging society. Since then, aging has become the main theme of China’s population changes. The seventh census data shows that China’s aging rate reached 13.5% in 2020. Based on the average aging rate over the past 20 years, China’s aging rate exceeded 14% in 2021, indicating its entry into an aged society. Any data adjustments that might slightly delay this milestone will not change the overall judgment that China has entered an aged society. What needs to be discussed is the economic impact of China’s transition from an aging society to an aged society, how it differs from the impacts observed to date, and its significance.

中国的老龄化率在2000年即达到7.0%,标志着进入了老龄化社会。从那以后老龄化就成为中国人口变化的主旋律。第七次人口普查数据显示,中国的老龄化率在2020年达到13.5%。如果按照过去20年的老龄化平均速度,中国的老龄化率在2021年即超过14%,标志着进入老龄社会。即便出现任何数据上的调整,使这个标志性的时刻略微延迟,也不会影响做出中国进入老龄社会的总体判断。需要讨论的是,中国从老龄化社会进入老龄社会的转折,究竟会出现什么样的经济影响,这个影响的性质与迄今所观察到的影响有什么不同,以及这种影响的显著性。

After becoming an aging society in 2000, China’s aging speed was relatively moderate until 2010, and it still enjoyed a demographic dividend for a while. Only after the working-age population peaked in 2010 did the pace of aging accelerate. Between 2010 and 2020, the primary challenge for China’s economic growth came from the supply side. The negative growth of the working-age population led to reversals in the supply and allocation of production factors, causing a significant and persistent decline in the potential growth rate. During this period, the actual growth rate was consistent with the potential growth rate, meaning there was no demand-side shock constraining economic growth (Cai, 2021). However, once China enters an aged society, it will face new and severe demand-side challenges.

应该说,自2000年进入老龄化社会后,中国的老龄化速度在2010年之前相对平缓,仍然享受了一段时间的人口红利。只是在2010年劳动年龄人口达到峰值之后,老龄化速度才加速攀升。在2010—2020年间,中国经济面临的增长挑战主要来自供给侧,即伴随着劳动年龄人口负增长,生产要素供给和配置均发生逆转性变化,导致潜在增长率的显著且持续性下降。在这期间,实际增长率与潜在增长率是相符的,意味着没有出现制约经济增长的需求侧冲击现象(Cai, 2021)。然而,一旦中国进入老龄社会,则将面临崭新且严峻的需求侧挑战。

To better position China’s aging population and understand the reality and severity of new challenges, it is worthwhile to compare China’s experience with that of Japan (Figure 3). Japan entered an aging society with an aging rate of over 7% in the early 1970s and entered an aged society with an aging rate of over 14% twenty years later in the early 1990s. In 1995, as Japan’s aging rate reached 14.3%, its working-age population also peaked. It was also from the 1990s that the Japanese economy entered its “lost decades.” Research indicates that from the 1990s to 2010, or during the “lost two decades,” the primary challenge for Japan’s economic growth was the vanishing demographic dividend, causing supply-side shocks. Only as Japan approached its population peak in 2010 (when the aging rate also reached 22.5%) and during the subsequent negative population growth did Japan’s economy face more apparent demand-side shocks, exhibiting characteristics of economic growth “long-term stagnation” or “Japanization” (Cai, 2021a).

为了更清晰地给中国人口的老龄化做出一个定位,以便认识面临新挑战的现实性和严峻性,不妨与日本的经历做一个对比观察(图3)。日本早在20世纪70年代初便进入老龄化率超过7%的老龄化社会,20年后于90年代初进入老龄化率超过14%的老龄社会。1995年,日本在老龄化率达到14.3%的同时,15~59岁劳动年龄人口达到峰值。也正是从20世纪90年代开始,日本经济进入其“失去的年代”。研究表明,在20世纪90年代到2010年之前,即在“失去的二十年”期间,日本经济增长面临的主要还是人口红利消失造成的供给侧冲击,只是在逐步接近2010年的人口峰值(当年老龄化率也达到22.5%)的过程中,以及在随后的人口负增长期间,日本经济才遭遇到更为明显的需求侧冲击,并且呈现出经济增长“长期停滞”或“日本化”的典型特征(蔡昉,2021a)。

Japanese economists once used four characteristics to describe the phenomenon of economic “Japanization,” or the characteristic manifestations of Japan’s economic stagnation. They are: 1. The actual growth rate is consistently below the potential growth rate. 2. The natural real interest rate is below zero, and also lower than the actual real interest rate. 3. The nominal (policy) interest rate is zero. 4. There is deflation or a negative inflation rate (Ito, 2016). This is consistent with the summary made by other economists, especially the representative figure of this theory, Summers, when discussing how aging leads to long-term economic stagnation worldwide. The insight derived from this is, as Japan, once the world’s second-largest economy, demonstrated upon becoming a super-aged society, deepening aging and negative population growth pose a significant demand-side shock to a country’s economic growth. It manifests as the overall social demand becoming a routine constraint on economic growth, often resulting in an actual growth rate that is below the potential growth rate.

日本经济学家曾用四个特征来刻画经济“日本化”现象,或者说日本经济停滞的特征性表现,即:第一,实际增长率长期低于潜在增长率;第二,自然真实利率低于零,也低于实际真实利率;第三,名义(政策)利率为零;第四,通货紧缩或负通货膨胀率(Ito, 2016)。这与其他经济学家特别是这个理论的代表性人物萨默斯,在探讨老龄化导致世界经济长期停滞时所作的概括基本一致。由此得出的启示是,正如作为曾经的第二大经济体日本在率先进入极度老龄社会表现出的那样,老龄化加深和人口负增长,给一个国家的经济增长带来巨大的需求侧冲击,表现为社会总需求成为常态的经济增长制约因素,以致经常性地出现实际增长率低于潜在增长率的负增长缺口。

China’s total fertility rate had already dropped below the replacement level of 2.1 in 1992 and continued to decline thereafter. This means that, after experiencing the inertia of population growth for a shorter or longer time, China’s population will eventually peak. In fact, the natural population growth rate has continued to decrease significantly since reaching its peak of 16.61% in 1987, and by 2020, it had already dropped to 1.45%, just one step away from the population peak. The transition to an aging society and an era of negative population growth poses challenges to the Chinese economy. The challenges are not just from the disappearing demographic dividend causing enhanced supply-side shocks, but also from the intensifying combination of supply and demand-side shocks. Moreover, the constraints on demand are increasingly becoming the main challenges facing economic growth. Among the many tasks to cope with these overlapping shocks, promoting the fertility rate to return to the replacement and expected levels is undoubtedly a long-term task requiring historical patience. However, given that this task also aligns with the goal of promoting common prosperity and can improve people’s livelihoods and stimulate consumer demand, it should be undertaken as soon as possible and pursued vigorously.

中国的总和生育率早在1992年就降低到2.1的更替水平之下,并且在那之后继续处于下降的过程。这就意味着在经历或长或短时间的人口增长惯性之后,中国人口终将到达峰值。事实上,人口自然增长率自1987年达到16.61‰最高点之后持续且大幅降低,2020年已经降至1.45‰,距离人口峰值只有一步之遥。进入老龄社会和人口负增长时代这个变化,给中国经济带来的挑战,不仅是正在经历的人口红利消失造成的供给侧冲击的增强,而是进一步加剧的供给侧冲击与需求侧冲击的叠加,并且需求制约将日益成为经济增长面临的主要挑战。在应对这种叠加性冲击的诸多任务中,促进生育率向更替水平及期望水平回升,固然是一个长期的任务,需要有足够的历史耐心;然而,鉴于这项任务也与促进共同富裕目标具有相同的方向,同时可以达到改善民生、促进消费需求的效果,因此,应该尽早着手并不遗余力地予以推进。

IV. Breaking the Fate of China’s Extremely Low Fertility Rate

四、破除中国极低生育率的宿命

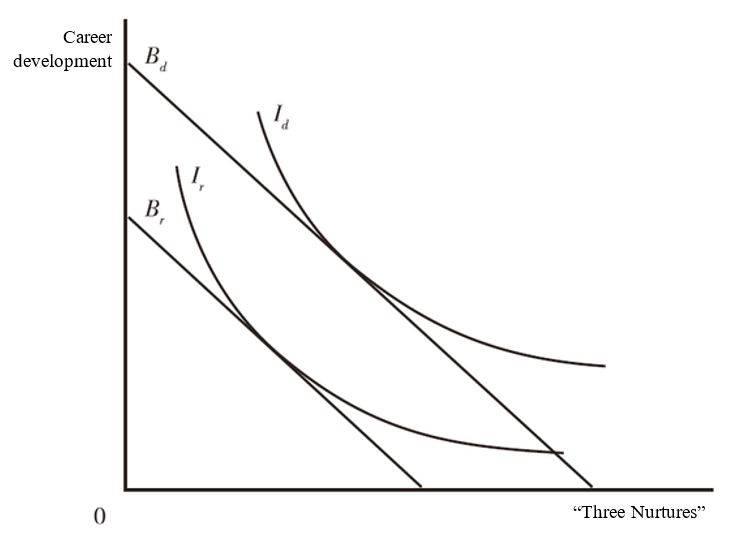

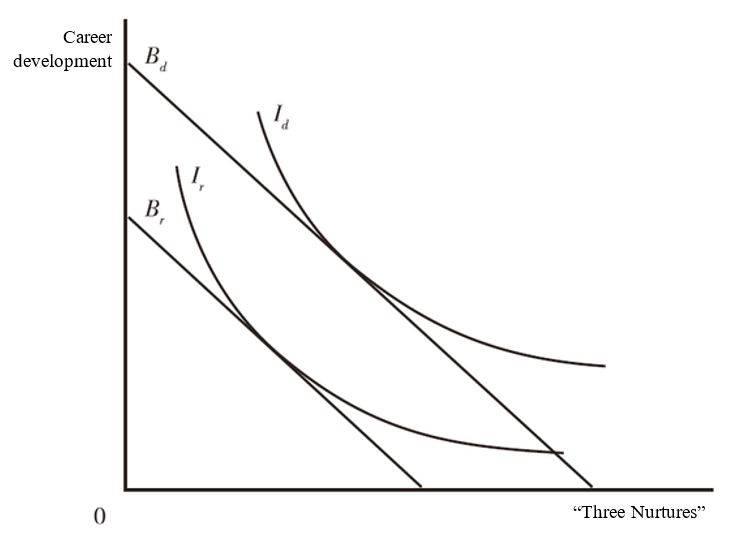

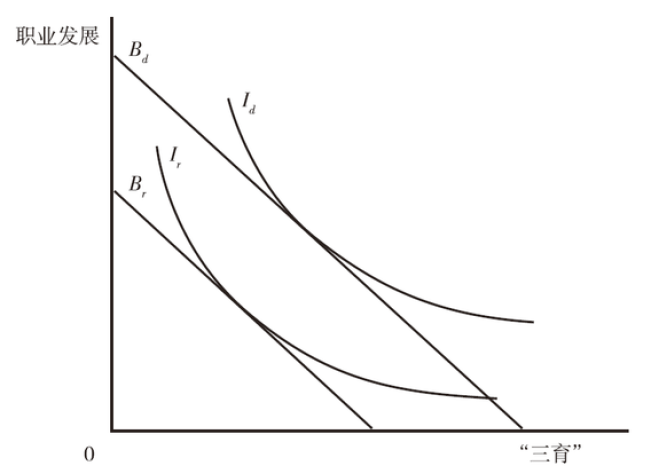

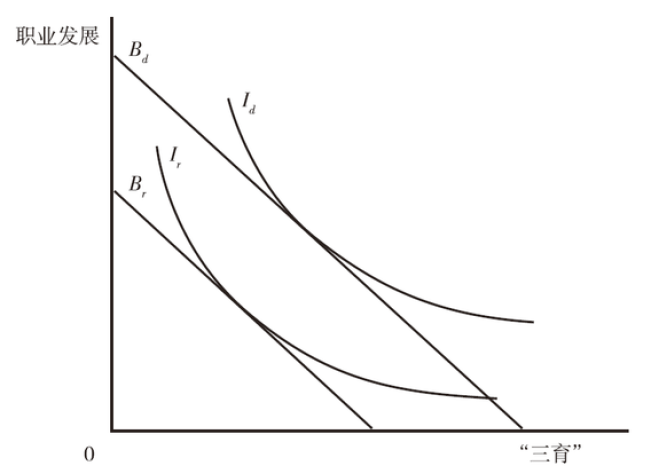

Based on the above analysis, the following hypothetical judgments can be made and further verified: 1. International experience has shown that under very high levels of human development and gender equality, fertility rates tend to converge from very low levels to the replacement level of 2.1. 2. Chinese families still have varying degrees of unmet fertility desires, so there is unique potential for the fertility rate to rebound from its current extremely low level. 3. By focusing on improving the level of basic public services and promoting gender equality, creating a more agreeable balance between career and “Three Nurtures” (childbirth, child-rearing, and child education) both socially and within families, China’s total fertility rate is expected to recover. Based on these hypotheses, this article uses Figure 4 to illustrate the trade-offs Chinese families make between career development and the “Three Nurtures.”

根据上文分析,可以做出以下假说性的判断,同时予以进一步的检验:第一,国际经验已经显示这样的趋势,在很高的人类发展水平和性别平等水平条件下,生育率趋于从过低水平向2.1的更替水平收敛;第二,中国家庭仍然具有在或大或小的程度上未得到满足的生育意愿,因而生育率具有从目前极低水平向上反弹的独特潜力;第三,着眼于提高基本公共服务水平和促进性别平等,在社会范围和家庭内部创造更为合意的职业与“三育”(生育、养育和教育子女)之间的平衡,中国的总和生育率有望得到恢复。按照以上假说,本文以图4来说明中国家庭在职业发展和“三育”之间的取舍权衡关系。

This article assumes the existence of an indifference curve Id, which corresponds to having 2.1 children. Every point on this curve meets the desired fertility level and the family’s career development goals, and it can be called the “Desired Family Development Indifference Curve.” To achieve the family utility on this combination, families need to have corresponding time and income. Here, this condition is expressed as the family resource budget line Bd and is called the “Desired Family Budget Line.” The tangent point between Bd and Id represents the ideal choice for family development that meets both career development and “Three Nurtures” expectations with the resources the family has. The “Desired Family Budget Line” usually includes professional achievements ensured by adequate social mobility, related income levels, a quality of life in line with societal standards, and social welfare matching the developmental stage.

本文假设存在着一个与生育2.1个孩子相对应的无差异曲线Id,这条曲线上的各个选项(所有的点)既符合家庭期望的生育水平,也符合家庭期望的职业发展目标,可以称之为“期望的家庭发展无差异曲线”。为了满足这个组合上的家庭效用,家庭需要具有与之对应的时间和收入,这里把这个条件表达为家庭资源的预算曲线Bd,并称之为“期望的家庭预算曲线”,其与Id的相切点即是家庭使用自身拥有的资源,同时满足职业发展和“三育”期望的家庭发展理想选择。这个“期望的家庭预算曲线”,通常包括由充分的社会流动予以保障的职业成就,以及与此相关的收入水平、与社会必要水平相符的生活质量,进而与发展阶段相符合的社会福利水平。

If the actual resources a family can access are insufficient to meet the desired level of family development, or if the family’s developmental capability is constrained by a budget line smaller than Bd, such as the “Constrained Family Budget Line” (represented as Br in the graph), the family can only match (be tangent to) an indifference curve smaller than Id, or the “Constrained Family Indifference Curve” Ir. This new choice space results in: First, the career development of family members, especially working-age women, is hindered or at least does not fully meet personal expectations. Second, the family’s income level is tight compared to reasonable expectations, resulting in a quality of life that is less than satisfactory. Third, the actual number of children born is below the desired level, meaning the real fertility desire under family resource constraints is lower than the ideal fertility desire without budget constraints.

如果现实的家庭可动用资源不足以满足家庭发展的期望水平,或者说家庭发展能力受到一个比Bd小的家庭预算曲线,譬如可以称为“受到制约的家庭预算曲线”(即图中Br)的制约,则家庭只能以此预算曲线去对接(相切)小于Id的无差异曲线或“受到制约的家庭无差异曲线”Ir。这个新的选择空间便产生以下结果:第一,家庭成员特别是其中的劳动年龄女性职业发展受到阻碍,或者至少不尽符合本人的期望水平;第二,与合理的预期相比,家庭的收入水平颇显拮据,生活质量不尽如人意;第三,实际生育的孩子数低于期望的水平,或者说受家庭资源约束下的现实生育意愿,低于假设不存在过紧预算约束的理想生育意愿。

Unfortunately, the tightness of family budgets relative to the stage of economic development, which constrains career development and reduces the willingness to give birth, resulting in obstacles to family development, is not hypothetical. It is the unfortunate reality many Chinese families, especially young couples, face. In a previous study, the author examined the labor income and unpaid labor proportions of Chinese households during women’s reproductive ages (15-49) and peak reproductive years (20-34). It was observed that neither male nor female workers reached their career status and income peak throughout their prime reproductive years. At the same time, women’s time spent on unpaid domestic work and caregiving activities has been increasing (Cai Fang, 2021c). This aggregate situation, translated into the actual status of young families in real life, means they face the tightest financial and time budgets, creating a difficult trade-off between career and the “Three Nurtures.

不幸的是,家庭预算相对于经济发展阶段过于拮据,从而制约职业发展、降低生育意愿,最终表现为对家庭发展的阻碍,并不是一种假设的情形,而是目前中国很多家庭特别是年轻夫妇面临的无奈现实。在此前的一项研究中,笔者结合不同的调查数据,观察在女性的生育年龄(15~49岁)和生育旺盛年龄(20~34岁)期间,中国居民家庭的劳动收入和无报酬劳动比例情况,发现在整个生育旺盛期,无论男女劳动者均未达到职业地位和收入水平的高点。与此同时,女性从事家务劳动和照料活动等无报酬劳动的时间却节节上升(蔡昉,2021c)。把这种加总的情形转化为现实中年轻家庭的实际状况,意味着其面临着最为拮据的财务和时间预算约束,存在着在职业与“三育”之间的窘迫取舍替代。

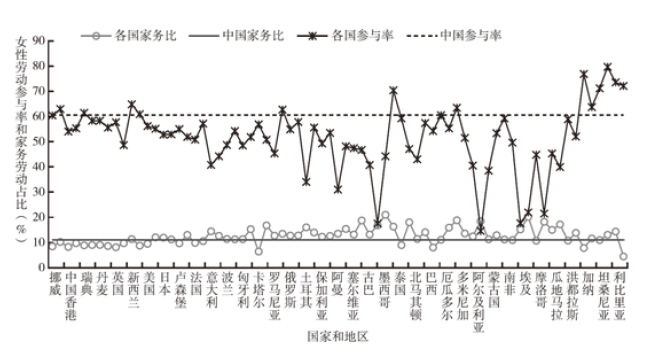

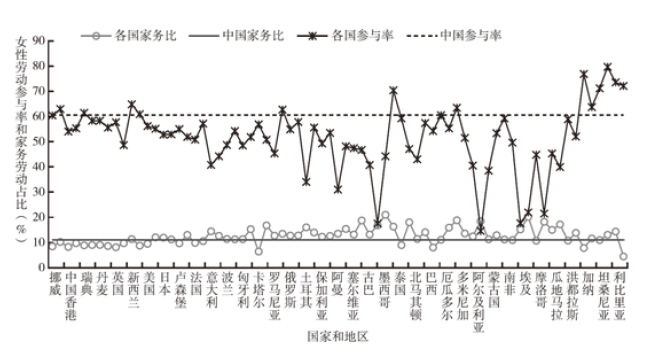

Arguably, this condition is characteristic of a particular developmental stage, especially closely related to a certain level of human development. Based on data from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP, 2020) and appropriate estimates, this article examines the labor participation rate of women and the proportion of time spent on domestic labor, comparing China with other countries and regions (Figure 5). Using 24 hours a day as a benchmark, Chinese women spend 11.1% of their time on unpaid domestic labor, slightly below the arithmetic average of 12.5% for all countries. However, the labor participation rate for Chinese women is as high as 60.5%, significantly above the arithmetic average of 51.6%. Moreover, Chinese women spend 2.6 times more time on domestic labor than men, indicating that their domestic labor burden is relatively heavy. This combination of employment responsibility and domestic labor burden is undoubtedly a major reason for the current low fertility rate in China.

可以说,这种状况是特定发展阶段的现象,特别是与一定的人类发展水平密切相关。根据联合国开发计划署(UNDP, 2020)的数据并进行适当的推算,本文可以观察女性的劳动参与率和从事家务劳动时间占比,并将中国与其他国家和地区进行比较(图5)。以每天24个小时这个总时长为基准,中国女性用于无报酬家务劳动的比例是11.1%,略低于各国该比例的算术平均值12.5%的水平。然而,中国女性的劳动参与率高达60.5%,显著高于各国的算数平均值51.6%的水平。同时又由于中国女性花费在家务劳动上的时间比例是男性的2.6倍,可见中国女性的家务劳动负担是比较重的。这种就业责任和家务负担都很重的状况,无疑成为目前中国的家庭生育意愿过低,并且实际总和生育率极低的重要原因。

Whether derived from existing international experiences or the current situation of balancing careers and the “Three Nurtures” in Chinese family development, we can conclude that China’s extremely low fertility rate is not predetermined. From Figure 4, by improving the level of human development, by moving the constrained family budget line to the desired family budget line level (moving from Br to Bd), reaching a higher level of utility satisfaction (raising the family indifference curve from Ir to Id), the fertility rate is expected to increase. However, according to international experience, enhancing human development is not merely about a composite human development index; it involves very specific conditions. For example, research by Myrskyla et al. (2011) shows that a sufficiently high Human Development Index combined with gender equality—ensuring the sufficiency of family resource budgets on the one hand and preventing discrimination against women in the trade-offs between career and the “Three Nurtures” on the other—constitutes a key driver for the rebound in fertility rates.

无论是从已有的国际经验,还是从中国家庭发展中职业与“三育”之间取舍权衡中的现状,都可以让本文得出中国极低生育率并非宿命的结论。从图4来看,通过提高人类发展水平,把受到制约的家庭预算曲线提高到期望的家庭预算曲线的水平,即从Br到Bd的移动,从而达到更高的效用满足水平,即家庭无差异曲线从Ir到Id的提升,生育率即有望得到提高。不过,根据国际经验,这里所说的提高人类发展水平,并不仅仅是从综合性的人类发展指数意义上而言,而是有着颇为严格的具体条件。例如,Myrskyla et al(2011)的研究显示,足够高的人类发展指数与性别平等程度的结合——一方面确保家庭作为一个整体资源预算的充足性,另一方面不造成家庭内部的职业与“三育”取舍权衡中对女性的歧视——构成生育率回升的关键驱动力。

V. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

五、结语和政策建议

The decline in China’s fertility rate is the result of rapid economic and social development during the reform and opening-up era and is in line with general trends. At the same time, the consequences of a low fertility rate and its resultant deepening aging population have constrained economic growth. “The person who tied the bell must be the one to untie it.” An appropriate resurgence of the fertility rate to replacement levels requires further socio-economic development. According to international experience, the socio-economic development level mentioned here is more aptly represented by the Human Development Index (HDI). As designed, theoretically defined, and statistically measured, the HDI inherently unifies economic growth and social development. In promoting this approach, social mobility and government-provided social welfare should be organically integrated.

中国的生育率下降是改革开放时期经济社会高速发展的结果,也是符合一般规律的现象。与此同时,低生育率及其导致的老龄化不断加深的后果,也产生了对经济增长的制约效果。“解铃还须系铃人”,生育率适度向更替水平的回升也需要经济社会的进一步发展。根据国际经验,这里所说的经济社会发展水平,更恰当的表达指标即为人类发展指数。按照设计初衷、理论定义和统计方法,人类发展指数从内涵上是经济增长和社会发展的统一,在统计意义上是更加丰富反映经济社会进步诸多指标的一种集成,在促进途径上要求把社会流动和政府提供社会福利进行有机统一。

Since the Reform and Opening-up, China’s human development has been built upon rapid socio-economic development, focusing on safeguarding and improving people’s livelihoods during development. On the one hand, the market plays a decisive role in resource allocation, emphasizing incentives and efficiency in primary distribution. On the other hand, the government plays a significant role, especially in redistribution, emphasizing fairness. This system and mechanism are consistent with the requirements for promoting shared prosperity and serve as practical measures to break the “fertility paradox.” However, just as economic growth cannot automatically resolve income distribution issues via the “trickle-down effect,” promoting fertility through human development will not happen naturally. Policies should closely address the real constraints Chinese families face to achieve tangible results.

改革开放以来,中国的人类发展建立在经济社会高速发展基础上,立足在发展中保障和改善民生:一方面,市场在资源配置中发挥决定性作用,在初次分配领域突出激励和效率,另一方面,更好发挥政府作用,特别是在再分配领域更加强调公平。可见,这个体系和机制与促进共同富裕的要求是一致的,也是打破“生育率悖论”的实践抓手。然而,正如经济增长并不能指望“涓流效应”自动解决收入分配问题一样,通过促进人类发展推动生育率回升也不会是自然而然的,而需要针对中国家庭面临的现实制约,在政策实施中更贴近问题,才能取得实际效果。

The potential for China’s fertility rate to rebound is embedded in the following areas, and more targeted policy tools should be designed accordingly: 1. Among the factors that led to the decline in China’s fertility rate, there are both the regular driving forces of socio-economic development and the specific influence of the family planning policy. As policies continue to relax and supportive policies incentivize, the suppressed fertility desire will eventually be released. 2. China’s HDI has indeed risen quickly, reaching 0.765 in 2019, ranking among “high human development levels.” However, the fertility rate turnaround is still some way off. Typically, a rebound in fertility rates occurs when the HDI is between 0.80 and 0.85, which is in the “very high human development” category. 3. Alongside the general improvement in the HDI, it is crucial to focus on enhancing gender equality, which will create more direct conditions for reversing the declining fertility rate. China has a good foundation in this regard, but there is still a long way to go for further improvement.

中国生育率回升的潜力蕴藏在以下方面,更有针对性的政策工具也应该据此进行设计:第一,在推动生育率下降的中国因素中,既有经济社会发展这个规律性的驱动力,也有计划生育政策的特殊驱动力。随着政策的不断放宽和辅助配套政策的激励,那部分被抑制的生育意愿终究会被释放出来。第二,中国的人类发展水平固然提升很快,2019年已经达到0.765,位于“高人类发展水平”的行列中,并且人类发展水平的排位比按购买力平价计算的人均GDP排位更加靠前;但是,距离生育率可能回升的转折点水平仍然有差距。一般来说,生育率触底并且回升的情形,至少要发生在人类发展指数达到0.80~0.85之间,这属于“极高人类发展水平”的行列。第三,在人类发展水平一般性提高的同时,还需要特别关注提升性别平等程度,才能创造出生育率下降的更直接条件。这方面,中国虽有良好的基础,但进一步改善还任重道远。

The 19th Party Congress proposed continuous progress in ensuring that children are raised, students are educated, workers earn, the sick are treated, the elderly are cared for, everyone has a place to live, and the vulnerable are supported. These seven “provisions” are consistent with the direction of improving the HDI and providing more extensive coverage for basic public services for residents. In response to new challenges and demands of the new development phase, the tenth meeting of the Central Finance and Economics Commission emphasized promoting shared prosperity in high-quality development, striking a balance between efficiency and equity, and building a coordinated foundational system for primary, secondary, and tertiary distribution. In general, China has entered a phase of development where redistribution efforts are significantly increased, and the social welfare system is rapidly established. Specifically, China, under the unique condition of aging before becoming wealthy and having a very low fertility rate, has an urgent need to increase the level of basic public services and equalization, aiming to boost the fertility rate back to the desired level. As the most populous country, China has experienced the largest labor movement and demographic shift in human history and can also achieve the largest scale of fertility rate rebound.

党的十九大提出在幼有所育、学有所教、劳有所得、病有所医、老有所养、住有所居、弱有所扶上不断取得新进展的要求,这七个“有所”既与人类发展水平的提高方向是一致的,也对居民的基本公共服务内容有更为广泛的覆盖。顺应新发展阶段的新挑战和新要求,中央财经委员会第十次会议强调,在高质量发展中促进共同富裕,正确处理效率和公平的关系,构建初次分配、再分配、三次分配协调配套的基础性制度安排。从一般规律来看,中国已经进入再分配力度明显提高、社会福利体系加快建设的发展阶段;从特殊针对性来看,中国在未富先老国情下形成的极低生育率,提出了通过提高基本公共服务水平和均等化,促使生育率向期望生育意愿回升的紧迫需要。中国作为人口规模最大的国家,曾经经历过人类历史上最大规模的劳动力流动和最大规模的人口转变,也可以创造最大规模的生育率回升。